Accurately modeling and rendering the ocean is highly intense from a computational perspective – but it’s considerably harder to accurately portray an artificial simulation of the human face, according to NVIDIA CEO Jen-Hsun Huang in his opening keynote address at the GTC 2013 conference in San Jose.

Human faces contain a subtlety that’s incredibly difficult to capture. Consider the wide range of skin textures, pore sizes, bumps, humps, colors, and other features that all have to interact in a completely natural manner in order for the illusion to hold. And that’s before we even think about modeling beards, goatees, and the like.

Anyone attempting to build a believable human facsimile also has to beware of the “uncanny valley.” This is a school of thought that says human copies which are almost – but not quite – perfectly human can cause big-time revulsion in us real humans.

(I would submit a picture of Carrot Top as proof positive that this is true. I’m sure you can come up with your own examples of real people who have gone over the uncanny cliff into the valley of revulsion. Spend a couple of hours on it today; it’s important, and sort of scientific too.)

Modeling the perfect human face is something that NVIDIA has worked on for years. Their best attempt (until recently) was Dawn, the fairy-like gal in the picture at above. This picture doesn’t do her justice; she truly does look realistic. The skin tone and texture is incredibly lifelike and attractive. Her hair moved in exactly the right way as the wind gently blew across her delicate brow. Sure, the bat ears detract a bit from the overall “realness” but certainly weren’t a deal-breaker for me.

The illusion fell apart when Dawn started to move. Her body motions were somewhat jerky and unnatural, despite all of the technology rendering her and the sophisticated programming that dictated her movements. When her face reflected emotions they were abrupt and, again, just not quite right. She was in that uncanny valley for sure, but still pretty cute.

The best way to imbue an artificial human with real human movements is, of course, to apply some technology in the form of hardware and advanced software. On a light stage, 156 cameras roll video as a genuine human moves around, extracting complete 3-D geometry of every move. Then you run the real human through 30 or so different facial expressions, recording every detail from nearly every angle. (Are there really 30 facial expressions? I only have six or so… maybe seven on a good day.)

This exercise yields around 32GB of data, which Faceworks compresses and distills into 400MB that can be used programmatically to generate facial expressions just like a real human’s. Combining the power of NVIDIA’s new Titan graphics card and their Faceworks software, their latest attempt – Digital Ira – is orders of magnitude better than Digital Dawn on her best day.

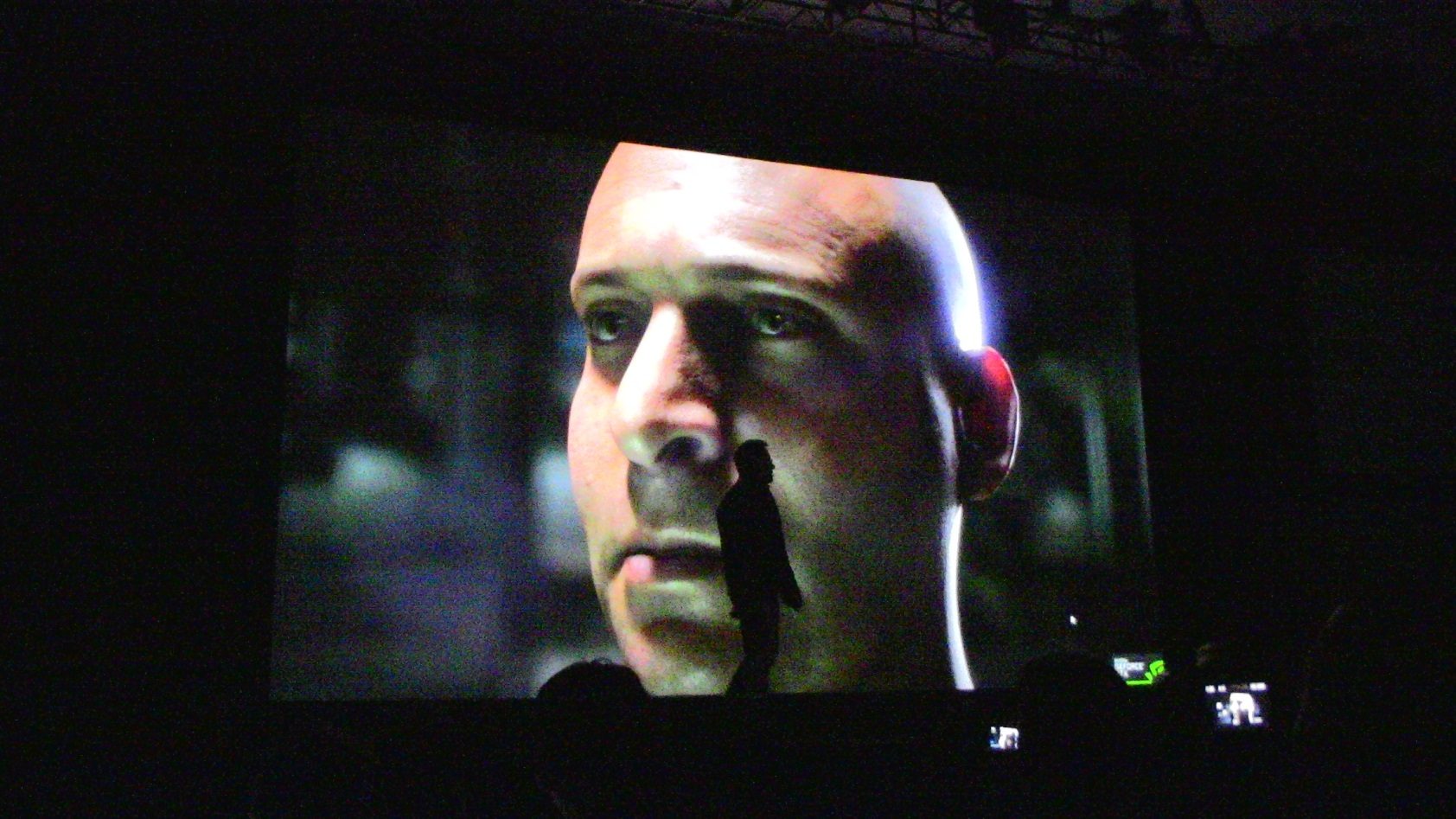

Pictured here with Huang in the foreground, Ira is damned realistic. Every detail of his face looked natural and accurate to me and everyone else in the room. (I didn’t actually ask everyone else, but I’m sure that if they disagreed with me, they’d let me know.)

When Ira worked through a range of emotions and facial expressions, the movements were completely natural, if a little hurried (which was due to the speed of the demo more than anything else, I think.) The details were just “right,” and the transitions from emotion to emotion were smooth and, again, natural.

But Ira really jumped the chasm from digital Vin Diesel to real deal when he started talking. His speech was fast-paced yet completely realistic. He was a little upset that his morning fruit yogurt had too much fruit and not enough yogurt, but that’s something all of us have raged about at some point or another.

It takes some power to make Ira so damned believable. He’s rendered on NVIDIA’s newest Titan graphics card, a 2,600-core behemoth sporting 7.1 billion transistors which is, according to Huang, the most complex semiconductor device ever manufactured. On the software side, there’s an 8,000-instruction program that articulates Ira’s geometry.

So how much compute power does it take for Ira to keep it real? Quite a bit. Here’s some of the math. First, if you figure that each instruction uses five floating point operations, we’re looking at 40,000 ops for each pixel that undergoes a change.

Assuming that he’s changing half the screen at a time, and then multiplying by the refresh rate of 60 Hz, you come to the conclusion that Ira needs around 2 Teraflop/sec to sustain his amazingly lifelike façade.

And the effect is truly amazing. He was animated, but not overly so; he was real. So how is this going to be used in the real world? I bet that Hollywood will definitely be interested. Huang discussed an idea about using this technology for virtual meetings, but I’m not so sure I see that as an early use.

On second thought, if Ira were to video call me and demand that I send him some money, there’s a pretty good chance I’d pay up. It was that good a human representation. Plus I’m sort of timid anyway.